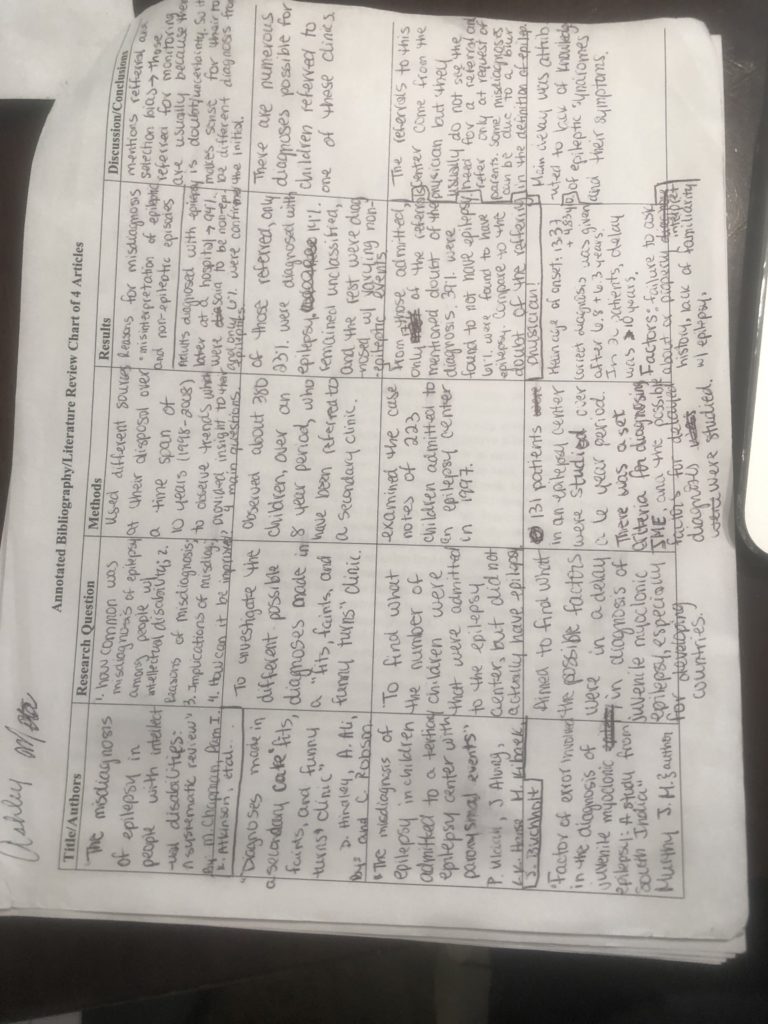

This assignment was a Literature Review. I chose the topic of “misdiagnosis of epilepsy” after I was it mentioned in a pediatric journal. In this assignment I reviewed 4 different articles to explore the main factors which led to the common misdiagnosis of epilepsy. Once I found the main components listed, in nearly all of the articles, I chose those factors as the subheadings for the Analysis portion of the paper. Analysis of those factors allowed for an inference to what the solution to the problem of misdiagnosing epilepsy, which was the basis of the conclusion.

Factors

Resulting in the Misdiagnosis of Epilepsy: A Literature Review

ABSTRACT

The

condition of epilepsy is one that has many different symptoms and is commonly

misdiagnosed. Epilepsy misdiagnosis can be seen through labeling a

non-epileptic condition as epilepsy or an epileptic condition being labeled as

being non-epileptic. The major factors leading to misdiagnosis are 1) confusion

between epileptic symptoms and non-epileptic episodes, 2) misinterpretation of

the results from different clinical tests such as EEGs and MRIs, and 3) the lack

of referral to epileptic centers based on the certainty of doctors in their

initial diagnoses. The misdiagnosis of epilepsy has a major implication for the

treatment which patients receive- in which they might be getting inappropriate

treatment for a condition they do not possess. A possible solution to lessen

the extent to which epilepsy is misdiagnosed can be to always refer

epileptic-like cases to a center which specializes in epilepsy, so that a

diagnosis is more accurate.

INTRODUCTION

Epilepsy is a serious condition which has

different symptoms, among which seizure is the most common. The disturbance in

brain activity that is caused by the symptoms of epilepsy can be harmful to the

body and brain. Therefore, once an epileptic diagnosis is made, actions for

treatment should be taken right away. Treatment for epilepsy can be different

anti-epilepsy medication. While epilepsy is a very serious condition, there are

accounts of common misdiagnosis of epilepsy. Misdiagnosis of epilepsy can be seen

in two forms: one is diagnosing a condition as epilepsy, when it is not, or

diagnosing another condition when it is epilepsy. In this literature review, a

different number of studies will be analyzed and compared to target which

factors contribute to the common misdiagnosis of epilepsy. The aim is to

pinpoint those factors and identify a possible solution so that the rate of

misdiagnosis can be reduced. This topic is of great importance because a

misdiagnosis of epilepsy can have many undiscovered implications for the

patient receiving the wrong diagnosis. When thinking of the importance of treatment

for epilepsy, a possible implication of misdiagnosis is that a person will not

receive the proper treatment for the treatment they possess- whether it be

epilepsy or another condition. Additionally, a person can be treated for an

illness they do not have and experience unknown side effects. With the analysis

of the main factors leading to the misdiagnosis of epilepsy, the implications

can be known, and a possible solution can be established.

ANALYSIS

Common Non-Epileptic Events and Symptoms Confused with Epilepsy

There are many different

diagnosis possibilities that can be assigned to symptoms common to epilepsy,

among which some were syncope, migraines, daydreaming, night terrors, psychological

episodic spells, tics, staring, dystonia, and disturbances during sleep (Hindley

et al 2006; Uldall et al 2006). Syncope is the most common non-epileptic event

that is mistaken with epilepsy (Hindley et al 2006; Fattouch et al 2007). Two

of the most notable differences between epileptic events and non-epileptic

events were that non-epileptic events were situational, meaning that they were

triggered by a specific event or activity, and that non-epileptic episodes

could be interrupted (Hindley et al 2006).This shows that even if symptoms seem

to be the same for epileptic and non-epileptic episodes, there are other factors

that could come into play which could aid in differentiating the two. Fattouch (2007)

supported this idea with the use of a questionnaire and scoring system that differentiated

between epileptic seizures and syncope. The questionnaire asked different

questions and each question had a specific scoring where it added points or

subtracted points. Some of the questions were if there was unresponsiveness

during the spell, if there was sweating before the spell, and if the spell was

associated with prolonged sitting or standing. The question regarding unresponsiveness

during a spell gets a point, going towards the characteristics of an epileptic

seizure, and sweating before a spell or the spell being caused by prolonged

sitting or standing loses two points, going away from epileptic seizure and

moving towards a syncope diagnosis. These three characteristics depict examples

of how to distinguish between non-epileptic and epileptic spells using two of

the differentiating factors expressed by Hindley (2006).

These cases dealt

with an epileptic diagnosis being given to non-epileptic events. However, the

reverse can happen as well. The lack of knowledge regarding the symptoms of

epilepsy can lead to an improper diagnosis of an actual epileptic episode. In

other words, symptoms might be labeled as being non-epileptic when in reality

the patient possesses epilepsy. Murthy (1999) conducted a study for the factors

leading to delay in diagnosis of Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME) in South

India with 131 patients. The symptoms for JME are explicitly known; however,

the time span in which they appear can vary between each other. For example,

generalized tonic clonic seizures (GTCS) are often the first symptoms to appear

but the circadian relations to awakening from sleep might not be fully

manifested right away. Additionally, the appearance of absence seizures can

precede GTCS and myoclonic jerks by 4 to 5 years. If a doctor is unaware of the

time span and characteristics of the symptoms of JME, they might just give a

diagnosis of absence epilepsy and not even consider JME as a potential future

problem. If the contrasts between non-epileptic episodes and specific epileptic

seizures are not very well known, there can be an effect on the diagnosis given

to a patient.

Misinterpretation of Data: EEGs, MRI, Etc.

When in centers that

do not specialize in epilepsy, it is hard to accurately analyze the data

collected through different tests in order to give the proper diagnosis (Britton

2004 cited by Fattouch et al 2007; Uldall et al 2006). The study conducted by Fattouch et al (2007)

had a cohort of 62 subjects, 57 of which were found to have a definite

diagnosis of syncope. They were divided up into two groups to further analyze

their data accordingly. 30 of the patients had received a “definite epileptic”

diagnosis; they made up the syncopes misdiagnosed as epileptic seizures (SMS)

group. 27 of the patients were only suspected

of having epilepsy; these individuals were labeled as unrecognized syncopes

(US). 70% of the SMS patients showed abnormal EEGs and 37% showed some

alteration in their MRI findings. In the US group, 33% had EEG abnormality and

only 1 had an MRI alteration. These statistics showed that there were abnormal

results collected from the MRI and EEGs, however, all of the subjects had a

syncope diagnosis, despite those abnormalities.

Similarly, in

Hindley’s (2006) study, of 380 subjects, there were differing abnormalities found.

Abnormalities were reported in 84%

of the subject count. Of this group, 85% of them were abnormal at the first

testing, but for 15% a repeat EEG, sleep EEG, or prolonged EEG was required. This

showed that due to uncertainty, a second testing might be needed for established

accuracy. 53% of the entire subject

population had computed tomography (CT) scans, out of which 23% showed some type

of abnormality. 52% had magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and 41% of this

group showed abnormality. The large presence of abnormalities could have misled

an epileptic diagnosis. However, only 23% of the subject population was

actually confirmed to have an epilepsy diagnosis.

This shows that

some doctors might be tricked by those abnormalities thinking that they point

directly to an epileptic characteristic of EEGs and MRIs. However, a proper

analysis is required to be able to distinguish between abnormal syncope, or

other non-epileptic events, results and definite epileptic results.

Doctors’ Certainty of Diagnosis:

The certainty of a

doctor on the diagnosis they are giving can deter from the proper steps being

taken to reach confirmation of an intended diagnosis. Some doctors

underestimate symptoms because they don’t want to give a harsh diagnosis such

as epilepsy for symptoms, which they are unclear of, to then have to retract

it. So, they prefer to label it as not being epilepsy, and then correct it

after the fact. (O’Donohoe 1994

cited by Hindley 2006) In Uldall’s (2006) et al study, 223 children were

observed, 17% of them had referrals where their doctor had doubt about their

epileptic diagnosis. From these uncertain referrals, 18% had confirmed epilepsy

and 82% did not have confirmed epilepsy. These doctors, worked similar to what

Hindley talked about, showing that it was better to have a non-epileptic or

uncertain diagnosis to then have it corrected. In contrast to this idea,

Uldall’s (2006) study also had 83% of their subject population with referrals

where their doctors were “without a doubt” certain of their epileptic diagnosis.

From these, 70% had a confirmed epileptic diagnosis and 30% did not actually

have epilepsy. The referrals from these doctors came mostly at the request of

parents. This shows that doctor’s could have such a strong feeling about their

epileptic diagnosis, despite their equipment and setting being inferior to that

of the epileptic centers, that 30% of patients would have been dismissed with

the wrong diagnosis. This is the perfect depiction of when the certainty of a

doctor could negatively impact the misdiagnosis of epilepsy.

CONCLUSION

When dealing with the diagnosis of

epilepsy, it is important to take into consideration the different symptoms and

possible non-epileptic diagnoses, as well as accurately decipher the clinical

data before a final diagnosis is made (Murthy 1999; Hindley et al 2006; Uldall

et al 2006; Fattouch et al 2007). Additionally, doctors should never be too

certain in their diagnosis, especially one that was made outside of an

epileptic center. Since major factors

established to affect misdiagnosis of epilepsy are often present in areas not specialized for epilepsy, it can be

inferred that a proposed solution to the misdiagnosis

of epilepsy is the referral of any episodes that even seemingly resemble

epilepsy to epilepsy centers before an epilepsy diagnosis is made (Murthy 1999; Hindley

et al 2006; Uldall et al 2006; Fattouch et al 2007). The major implications for

the misdiagnosis of epilepsy can be a delay in appropriate treatment for the

proper condition. The exact side effects of receiving treatment for the wrong

condition was not explored by these researchers; therefore, that is an area for

possible future directions in this topic.

References:

Fattouch J., Di Bonaventura C.,

Strano S., Vanacore N., Manfredi M., Prencipe M., Giallonardo A.T. 2007.

Over-interpretation of electroclinical and neuroimaging findings in syncope

misdiagnosed as epileptic seizures. Epileptic Discord. 9(2)(170-173)

[Internet][Accessed May 8 2019]

Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d2f5/2e5e508d5cb5fbae52f1d0256a4759220345.pdf

Hindley D., Ali A., Robson C. 2006.

Diagnoses made in a secondary care “fits, faints, and funny turns” clinic. ADC.

91(3)(214-218). [Internet] [Accessed April 15 2019]

Available from: https://adc-bmj-com.clinical-proxy.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/content/91/3/214

Murthy JM. 1999. Factors of error

involved in the diagnosis of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: a study from South

India. Neurology India. 47(3)(210-213). [ Internet] [Accessed April 13 2019]

Available from: http://www.neurologyindia.com/article.asp?issn=0028-3886;year=1999;volume=47;issue=3;spage=210;epage=3;aulast=murthy

Uldall P., Alving J., Hansen L K.,

Kibaek M., Buchholt J. 2006. The misdiagnosis of epilepsy in children admitted

to a tertiary epilepsy centre with paroxysmal events. ADC. 91(3)(219-221).

[Internet] [Accessed April 10 2019]

Available from: https://adc-bmj-com.clinical-proxy.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/content/91/3/219